What I think about birth centres: an interview

/Laura Iannuzzi is an Italian midwife, currently studying for a PhD at Nottingham University in England. After qualifying as a midwife in 2001 Laura has worked in different areas of practice, and since 2004 Laura has been employed by the University Hospital of Careggi, latterly at the Margherita Birth Centre. Laura's research topic for her study is 'An exploration of midwives' approaches to slow progress of labour in English and Italian birth centres'.

Laura emailed me and asked if she could interview me about my thoughts on birth centres-not for her study, but because she is interested in the relative success of birth centres in England. I agreed of course, as I usually interview others!

Dear Sheena, first of all thank you very much for your availability for this interview. As you know, this is for me a great pleasure and honour; you are indeed largely recognised as an inspirational midwife inside and outside UK. And it is quite intuitive to see why, given your apparent innate ability to communicate the beauty of midwifery, to capture and amplify voices of women and midwives from all over the world, to show that change is actually possible wherever, and to support any initiative aimed to improve midwifery practice, education and research.

We could discuss about many things, but today I would like to talk with you about birth centres and their management, taking the most from your experience. You worked in fact as Head of Midwifery in the East Lancashire Trust where your played a key role in the establishment of the Blackburn Birth Centre, one of the most successful freestanding birth centres in England.

1. As someone might not be familiar with the language and the models, how would you define/describe a birth centre? What are the main features that differentiate a birth centre from other birth settings (e.g. hospital labour ward, maternity houses, home)?

Thank you Laura. What an introduction…I am flattered and grateful, yet as always I am taken aback….

It’s a pleasure to answer your questions!

Birth centres are places where women who have no expected complications can go to give birth, in a calm, non-medical environment, to be cared for by midwives and support workers. There are two types of birth centres, Alongside Birth Centres (AMU) are situated on the same site as an obstetric unit, and Freestanding Birth Centres (FMU) are in a separate building to a hospital, in a community setting. Birth centres should be managed by highly skilled midwives, who carefully monitor women in their care, and encourage and support them to give birth at their own pace, with minimal interference.

In an attempt to describe my thoughts on how birth centres differ to hospital (obstetric unit) birth facilities, I want to tell you about a period of my midwifery career. During the 1980’s I worked for 9 years in a ‘maternity home’, which was the same as a birth centre, except the woman’s GP (family doctor) came to the birth. The maternity home was several miles away from the host hospital, so was ‘freestanding’. Working there taught me how to be a midwife, in the truest sense of the word. I learned from experienced midwives and the women who laboured and gave birth there. There were no electronic fetal monitors, and so I became proficient in using my midwifery skills, my eyes, ears and intuition to give safe, high quality maternity care. I saw women labouring un-interrupted; it became second nature to me to support normal physiological childbirth, and to witness the immeasurable joy and satisfaction of parents as they met their baby for the first time. They did it themselves. We had a progressive manager (Pauline Quinn OBE) who introduced birth mats and birth stools (this was in the early 1980’s)…women rarely used the bed except for resting and sleeping. As I mentioned, this was early in my career, and whilst I had witnessed ‘normal’ birth previously, it was in a hospital setting where women laboured on their backs, on beds that resembled those in an operating theatre. Normal birth mostly happened by chance in the hospital, for example if the woman came in advanced labour or was multiparous, or as a result of the midwife’s strategy to protect the woman from the rigid policies and protocols of active management of labour (O’Driscoll and Meagher 1986). When I returned to the hospital to work after the maternity home closed, I saw that there had been a radical shift in the way women were being cared for. Epidural anaesthesia for pain relief had been introduced, and caring for semi-paralysed labouring women was new for me. I felt like a nurse again, in in a critical care environment. From that time (1990) until now, I have witnessed first hand the increasing medicalisation of childbirth, where pregnancy and birth are pathologised, and risk averse practice dominates. Fear prevails, both from the maternity care workers perspective, and women using the service. Yet maternal and fetal outcomes have not improved during that time, indeed, there is growing concern of potential iatrogenic harm as a result of unnecessary medical intervention (Dahlen et at 2013, Renfrew et al 2014). I must be clear at this stage, that some interventions in childbirth are crucial, and life saving. The task we have in maternity services is identifying those women who really need it, not treating every pregnant woman ‘just in case’.

So birth centres for me provide the space for women to give birth safely and with the least interference, and they act as a catalyst for change.

2. What does it mean that birth centres are midwife-led structures?

It means that midwives, experts of normal physiological childbirth, provide care for childbearing women who don’t have expected complications, in an environment that supports them to labour and birth undisturbed. The midwives should be appropriately skilled, and able to recognise any deviation from the normal and respond and refer appropriately. Safe transfer of care, where collaboration and respect is the prevailing culture within the reciprocal service, is crucial.

3. Why should women and their partners consider a birth centre as place of birth for their baby?

The large study in England (Birthplace) revealed that birth centres are safe for mother and baby, and that giving birth in a non obstetric unit setting significantly and substantially reduces the chance of having an intrapartum caesarean section, instrumental delivery or episiotomy. These are crucial considerations, given the increasing Caesearian section (CS) rate, consequential potential iatrogenic damage, and financial costs. A recent Lancet paper (Renfrew et al 2014) cited a WHO study (Gibbons et al 2012) that estimated 6·2 million unnecessary Caesearean sections were being performed in middle and high-income countries. Avoiding unnecessary intervention in pregnancy and childbirth has been shown to lead to better outcomes for women, they have a quicker recovery and there is improved satisfaction (NCT, RCM, RCOG 2012). Women experiencing a normal birth are more likely to breastfeed, will require less postnatal care and are less likely to visit their doctor with postnatal complications.

Being afraid of childbirth is another important consideration (Ayers 2013), and documented reports of disrespect and abuse add to the picture (Birthrights 2013). However, women giving birth in midwife-led settings report feeling more satisfied with their birth experience, and that their birth positively influenced the way they felt about themselves (Birthrights 2013).

4. Do you think organisations should invest in birth centres? Why?

There is robust evidence that obstetric unit birth is not appropriate for women with low risk pregnancies. If women are more likely to have a normal physiological birth in a birth centre, and normal birth is a public health issue (Sandall 2004), then organisations should provide these settings for women with low risk pregnancies.

In addition, planned birth at home, in a freestanding midwifery unit, or in an alongside midwifery unit generates incremental cost savings compared with planned birth in an obstetric unit (Schroeder 2012). Further, occupancy rates for freestanding midwifery units (30%) were under half that of obstetric units (65%) and much lower than alongside units (57%).

5. As you probably know, while in Italy birth centres are still a rarity (it has been reported around 4-5 in the whole country) in UK there is an increasing presence of these models ( > 100). How would you explain this phenomenon? What factors contributed, in your opinion, to the onset and development of these midwifery models of care in your country?

Intuitively and anecdotally, midwives have always known that out of hospital birth is safe, and more satisfying for mothers, families and midwives. Because of this, midwifery innovators and leaders have striven to establish birth centres, and to promote and support home birth. The difference now is that we have strong, clear evidence to back up the knowledge.

Globally, maternity care workers and politicians are becoming increasingly aware of the human and financial costs associated with the escalating unnecessary intervention in childbirth in high and middle-income countries (Renfrew et al 2014). Because this can be addressed by providing midwife led settings for women to give birth, the draft Intrapartum Care NICE Guidance (2014) is advising low-risk nulliparous and multiparous women to plan to give birth in a midwifery-led unit (freestanding or alongside) as the rate of medical intervention is lower and the outcome for the baby is no different compared with an obstetric unit.

Maternity care leaders also considered midwifery skills. If midwives only work in obstetric led settings, with increasing unnecessary intervention rates, the skill and expertise needed to facilitate normal physiological childbirth become diluted. This compounds the already potentially catastrophic consequences of unnecessary intervention in childbirth (Dahlen 2013).

To demonstrate the reality of this phenomena, here is an exert from a letter recently sent by a student midwife in England, to the Royal College of Midwives (RCM), raising concerns about her lack of exposure to normal childbirth:

[I became very disheartened and concerned about my own experiences. As a student midwife, I completed my second year of training after having witnessed and participated in 52 caesarean sections, 16 instrumental deliveries and very sadly, only 11 normal deliveries. I can vouch for the fact this story is not unique and many students are having a chronic lack of exposure to normality. In fact what the ICM (International Confederation of Midwives) and RCM seemed to call 'normal', to me seemed like a fantasy, not the world in which I was training and learning. I was saddened to realise that I'm now a third year student and have never used intermittent auscultation in practice and have never seen a women give birth off her back].

I believe this is unacceptable.

6. It is a common belief, especially among those who would not advocate for birth centres, that these models are too expensive (and we know that none can ignore the global financial crisis) and provide care just to 'small privileged groups of women' compared to traditional hospital models. What is your opinion and experience about that?

The Birthplace study mentioned above provides evidence that centre birth is less expensive than obstetric unit birth, taking all aspects of the care of mother and baby into consideration. In East Lancashire in northern England, 30% of women give birth in a birth centre, and those women are from culturally and socially diverse communities. We cannot ignore the evidence we have of potential harm if we do not provide these services; nor the emerging evidence (Dahlen et al 2013). The issue of women using birth centre facilities if available is an important one. Pathways of care must support women making a decision to give birth in a birth centre, with midwives who work in them providing the information. I know this is one of the reasons why the birth centres at East Lancashire Hospitals mentioned above are so successful.

7. Given the international problem of the shortage of midwives, denounced by many organisations including the International Confederation of Midwives, it seems important both to lobby for more midwives for women and families, and to use the current resources at their best. In this situation, directors and managers might prefer to 'centralise' midwives in big labour wards rather than encourage their employment in new/different units... Did you come across this kind of debate? Do you think there is a room for birth centres in time of crisis? Why?

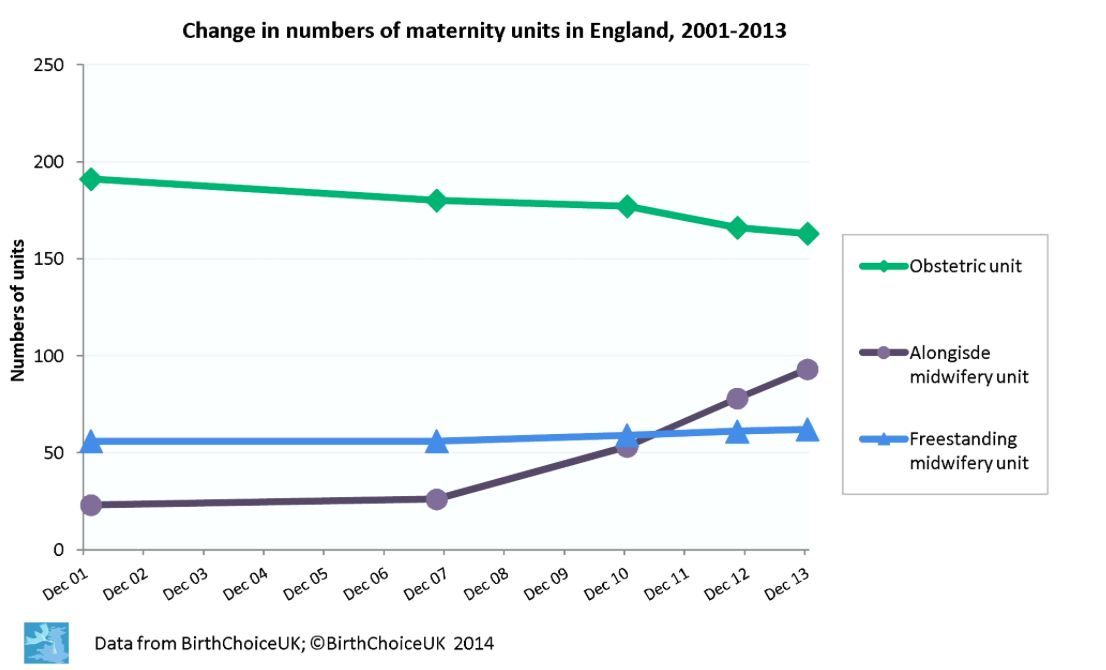

Yes, since the 1950/60s there has been the desire to centralize maternity care into hospital in the UK, and more recently reconfigurations of maternity services has seen the amalgamation of smaller maternity services into larger, centralized units. However, national policy drivers (DoH 2007) directed services to offer the choice of midwife led facilities, and the response has been positive with an increase in the number midwife led establishments (see BirthChoice UK chart below).

Other countries such as Catalonia are paying attention to the importance of childbirth as a measure of societal health, and to prioritise midwife led care, and choice (Escuriet & Oritz 2014).

The Birthplace Study is clear that it is less expensive for low risk women to give birth in a birth centre, which included the number of midwives needed to care for them. In fact, given the evidence of increased unnecessary intervention for low risk women giving birth in hospital, there are financial considerations for this. The model of midwifery care in all settings needs to be flexible and responsive to the need of the service, and there is no ‘one size fits all’. However, the general principle that the midwives ‘follow’ the women, i.e. they are able to work in all settings, helps with workforce planning and promotes safety.

8. Always connected to the shortage of midwives, anecdotally, some organisations seem to assume that as midwifery-led units are caring about low-risk women, there is less need for midwives than in obstetric units. What or who establishes the number of midwives needed in a setting? What are the criteria you used or you would suggest to calculate, even within a limited number of midwives, the minimum acceptable staffing especially thinking about birth centres?

I asked the Head of Midwifery, Anita Fleming, from East Lancs Hospitals NHS Trust in England (mentioned above) to help with this question, and her service provides 3 birth centres with 30% of women giving birth in the facilities. Anita said:

[Birthrate Plus (Ball et al 2013) provides guidance for midwifery staffing; it is advantageous to calculate the numbers of midwives needed for your service overall and not necessarily how those midwives are allocated to each area. Professional judgment is essential, and will depend on several things such as number of birth rooms and also on what other activity goes on there, in addition to birth. There needs to be enough staff to provide one to one care in labour and to retain safe numbers if a midwife goes on a transfer. We have a lot of other activity in our BC’s (checks, clinics, immunisations etc) to make best use of the midwives time when unit quiet; it isn’t appropriate for midwives to be sitting round waiting for women in labour. NICE is currently developing guidance staffing guidance for maternity settings which should be out for consultation in October / November this year, prior to publication of the final guidance in January 2015].

9. What are the current features you think should be reduced and which increased in order to improve maternity care?

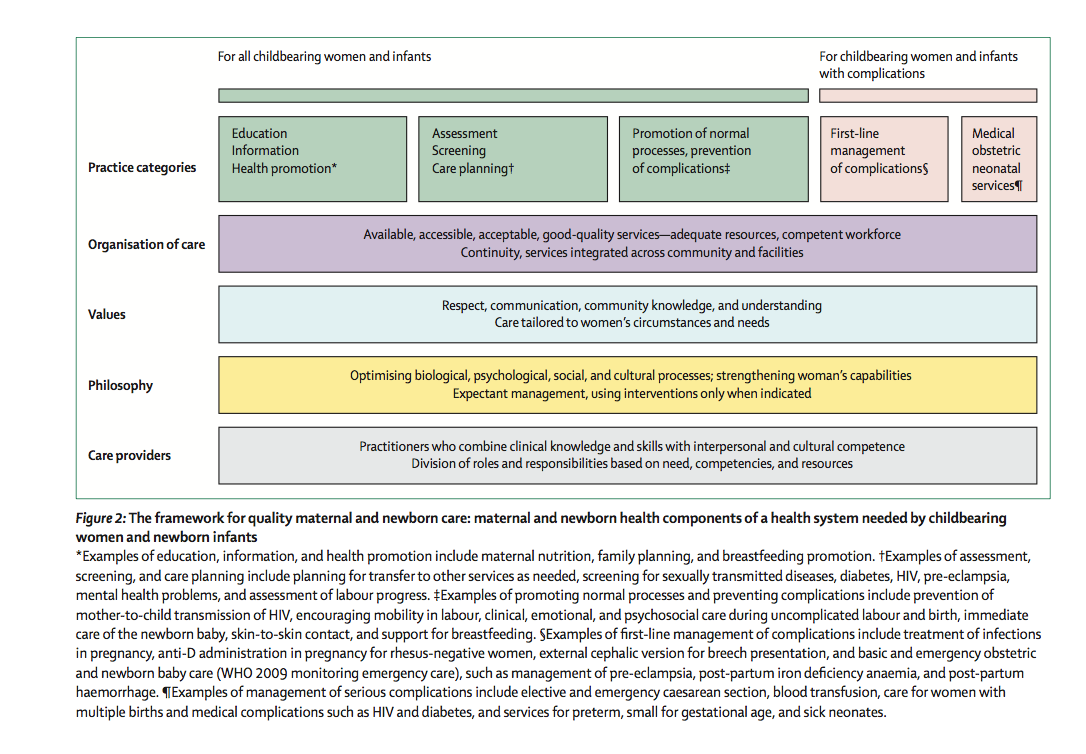

I am quite clear about this Laura. I think today’s maternity care systems are focusing so much on preventing risk, that they are blindly increasing it (Dahlen 2014). I believe we should try to reduce the ‘tick box’ culture, which focuses on ‘it’s done’, rather than trying to give individualised care based on building compassionate and trusted relationships both with women in our care, and all members of the maternity team. We are processing women through a strangled system, all the time being reminded to ‘protect ourselves’ against litigation and recrimination. This leads to fear and defensive practice that potentially increases serious harm. Governments and maternity care providers should examine the evidence and respond appropriately, and assess their maternity service on the global Framework for Quality Maternal and Newborn Care [see below] (Renfrew et al 2014). Leaders must also remember that where resources are limited, unnecessary medical intervention is more expensive, and financial costs unsustainable.

What is more important than the birth of a baby?

10. As you know, midwifery-led care and midwifery-led models where midwives work autonomously are highly supported by evidence but may be poorly supported in the reality of daily practice. I have in mind many realities in Italy where brilliant midwives are struggling with a highly-medicalised culture, but this seems to be true also in other more midwife-friendly environments, such as the English one. What are the facilitators and what the barriers to translate evidence?

In believe the key to the success of midwifery led models is for midwives work collaboratively with medical and academic colleagues, and to build trusted relationships. This approach, where possible, reduces the polarisation of models of care, where no-one benefits, least of all the woman and family using maternity services. For this to happen, all parties have to be willing to understand the part that they play in ensuring safe maternity care, and to respect and appreciate each other’s roles and philosophies.

11. Would you like to send a message to all the Italian midwives, especially to the ones that are currently struggling in seeing positive signs for the future of midwifery?

The maternity service where I worked has recently been awarded Maternity Service of the Year, by the Royal College of Midwives. Within the service there are 3 birth centres and an obstetric unit, and 6,500 babies are born each year. It wasn’t always like this. I remember times when we felt desperate-the climate was oppressive and hierarchical, and there was little hope for a positive future. A few of us were strong. We had passion and believed in woman centred care. We engaged academic colleagues who helped us to find and articulate the evidence, and were determined to change. The strength of leadership was changeable, so we tried to lead ourselves, and it worked. This took many years, it didn't happen over-night, and there were many disappointments!

Remember the change needs to start with you-don’t wait for others to do it.

Laura Iannuzzi can be found on Twitter

References (unlinked)

Ayers, S. (2013). Fear of childbirth, postnatal post-traumatic stress disorder and midwifery care. Midwifery 30:2 Feb pg 145-8

Dahlen H (2014) Managing risk, or facilitating safety? International Journal of Childbirth Vol 4, Iss 2

Department of Health (2007) Maternity matters: choice, access and continuity of care in a safe service. DoH London

O'Driscoll K, Meagher D (1986) Active Management 2nd Ed. London: Bailliere Tindall

Sandall J (2004) Normal birth: a public health issue Practising Midwife Jan 7 (1) Pp 4-5

Additional reading:

Coxon K (2013) Freestanding Midwifery Units: local, high quality maternity care RCM publication

https://www.rcm.org.uk/sites/default/files/FMU%20Mythbuster%20-%20Web%20Final.pdf